Developing evidence based policing: Building social capital

Susan Ritchie examines the case for developing evidence based policing to increase community engagement whilst making best use of shrinking resources.

Susan Ritchie examines the case for developing evidence based policing to increase community engagement whilst making best use of shrinking resources.

Categorising evidence

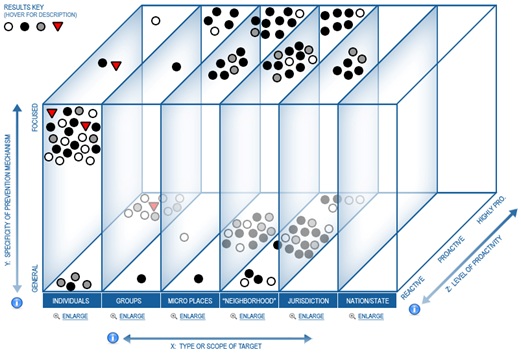

The Centre for Evidence Based Crime Policy provides a matrix developed by academics; it is a research-to-practice translation tool that organises all methodologically rigorous studies visually, enabling agencies and researchers to view the field of research, from its generalisations to its particulars. The matrix is used to understand the types of interventions used to reduce crime: a 3D model which categorises interventions as:

- Focused or general;

- Reactive or proactive;

- Targeted at individuals, groups or places

One hundred and thirty examples of police activity have been categorised along a spectrum of ‘being harmful’ (red triangle) to ‘effective’ (black circle). At a quick glance we can see that a lot of activity is conducted with individuals, but with limited evidence of effectiveness. Focused, highly proactive, place based initiatives show more promise with more evidence of effectiveness. The approaches used in those studies include increased patrols, door to door visits, reassurance policing, focused deterrence and problem solving – no surprises there you might argue.

Some might argue that the approaches considered to be effective are unsustainable in a policing world of reduced resources: how much would it cost year on year to deploy officers on door knocking duties, and to what end? If we are to believe the media, there will be less visible patrols as the cuts hit the frontline. Those on the frontline know that partnership working (and therefore meaningful problem orientated policing) is almost non-existent at the frontline, or at best it is ‘patchy’. So a more creative way of securing the same effect, but without continued deployment of officers, is needed. In other words policing needs an approach that helps communities work differently with police officers to manage and reduce demand, and one which builds the relationships between the two, so that intelligence is shared more effectively and informs planning and delivery.

Leadership and evidence (frontline and senior leadership)

It is the frontline who make the difference in policing so it is important that they are supported to turn innovation into evidence, and theory into meaningful practice. With training budgets slashed, and time being one of the rarest commodities, rarely can anyone commit time to anything other than reactive policing, despite the fact that Chief Constables and academics lament its introduction and continuance (Alderson, 1984; Reiner, 2000; Newburn, 2008) There is, therefore, a dilemma that PCCs are grappling with – how can they ensure the frontline is supported to change the practice of organisational delivery when time and resources are limited? How will they secure the best return on investment for the public who voted for them (and those that didn’t)?

I have argued elsewhere (see Fisher and Ritchie; 2015) that prioritising Waters (1996) ‘functional’ approach to policing prevents the frontline from building social capital and enhancing the ‘interactional’ element of Waters’ model of quality service in policing. The ‘micro places’ and ‘neighbourhood’ categories of the matrix above do not include research on building social capital despite there being evidence available (see Rosenfeld et al, 2001).

Greater Manchester Police and Durham Constabulary’s leaders followed their instinct that something needed to change in the way that they engaged with communities: they felt they weren’t developing the relationships and benefitting from the intelligence that they needed to keep people safe and prevent crime. They wanted a focused approach to building places where the community drives the approach to policing at a local level.

In the innovation thematic for CoPaCC I argued that there is no point in adopting these new techniques and approaches if there is no will to change the existing systems and structures: those few leaders that have witnessed and participated in this approach (frontline and senior) continue to grapple with delivery of the ‘what is’ and the ‘what could be’. They run the risk of undoing the hard work they put in, because the people in the system can’t respond to it or understand the input required in the short term (invest to save really is the phrase to use with social capital). When the momentum is lost, because leaders can’t decide whether to invest in this model of demand reduction, they end up having to start again (wasting public resources).

Those who have witnessed the effects of building social capital work tirelessly to make the case for what is essentially a ‘non police’ tactic, but one that requires the investment from PCCs to ensure the public can hold the police to account, beyond the election of a PCC. It is not a short-term vote winner: it is what Putnam calls a ‘slower, more subtle and harder to reverse’ approach to social change which focuses on ‘intercohort’ changes. It means you must have tenacity.

Intercohort changes are those social mores that are relaxed over generations (attitudes to violence, sexual behaviour etc.). As the ‘stricter’ and older generations pass away the ‘norms’ are relaxed and extended until we realise society has changed. By building social capital now, and raising the expectations around civic duty and active citizenship we have a chance of changing the relationship between citizen and state, for positive end. It is the moral imperative of public services to think beyond their own time of office.

Building the evidence base for social capital

If the refresh of democracy requires us to go beyond voting every four years, refreshing the relationship between police and communities requires us to go beyond our traditional approach to community engagement. Roadshows, ‘you said, we did’ communications, PACT meetings etc. are limited when it comes to a return on investment. They may help influence peoples response to a survey in the short term, but they won’t change the relationships between communities and between the community and the Police (Ritchie; (in press))

Building social capital is no straightforward task/finish exercise: it is (in my view) an ongoing moral requirement of our ‘public services’: “…depleted social capital contributes to high levels of homicide” (Rosenfeld et al, 2001) There is a library of research on the rationale for developing social capital, its impact and its measurement which can help us develop innovative tools and techniques but it is often ignored because it is not as easy as introducing initiatives that focus on individual, patrols or communications.

Last year Durham University evaluated a practical frontline police and PCC led approach to building social capital that found, amongst other positive results, that changing the practice of officers and the techniques they use reduces crime and increases resident cooperation. The approach was conducted as a Level 4 experiment on the College of Policing’s research ladder*. The control sites were not subject to displacement. The evidence is set out below:

| Area 1 | Area 1 Control site | Area 2 | Area 2 Control site | |

| Changes in Victim Crime | -31% | +5% | -14% | +39% |

| Changes in ASB | -11% | +2% | -22% | -2% |

The main driver for the significant changes appears to be the increase in social capital achieved (p-value =.010) This was measured using indicators that relate to communication and cooperation of residents to engage in collective action to overcome problems in their community, the level of crime reduction was significant. The University developed a measurement of social capital that they felt most suited policing from the literature. The evidence on that was equally positive and academically significant:

- The measurements were:

- Trust (feelings of trust, confidence and the ability to rely on other people – p=.020)

- Information Sharing (levels of open and honest communication and willingness to share information (p=.007))

- Vision (levels of shared vision and purpose and feelings of being partners in influencing the local area’s direction (p=.043))

- The evidence shows that when you increase social capital you will increase the ‘area potency’ which will in turn positively influence NI21 indicators (dealing with local concerns about anti-social behaviour and crime issues by the local council and police (p=.019)

- The same can be said with performance: when social capital increases it drives the increase in area potency and has a positive impact on performance

- Potency = ‘voice’, ‘cooperation with police’, ‘life satisfaction’ and ‘fear of crime

- Residents views on the potency of their local area increased significantly (p=.016) which suggests that residents believe their area has higher confidence and can solve problems itself, and achieve high quality outcomes

- Residents Voice behaviour increased between Time 1 and Time 2 (p=.022) which means they speak up and make suggestions to solve problems

PCC responsibility for changing the way we police

A new evidence base is emerging. Now that PCCs future is secured following the election of a Conservative government, they will have a moral and practical responsibility to change the direction of community engagement to one which is co-productive in reducing demand. They should be encouraged, by the evidence, to stop the pointless roadshows and the accompanying rhetoric, and instead stand bold and provide evidence that they are building social capital, rather than hoping communities will engage as a result of them telling rather than listening (see my blog on telling and listening).

If “honesty and trust lubricate the inevitable frictions of social life” (Putnam, 2000) then they must go beyond their current approaches of formulaic communications to a more sophisticated approach of ‘generalised reciprocity’. PCCs and Chief Constables must invest in the capacity building of their front line so that they can do this in practice, and when they have the evidence that it works they will have to change the current approach to the way in which we police British society.

References

Alderson, J.C. (1984) Law and Order. London. Hamish Hamilton

CoPaCC Thematic: PCCs and Innovation – June 2014 and Appendix

Fisher, A. & Ritchie, S. (2015) A functional shift: Building a New Model of Engagement ; Policing 101:114

Level 4: Comparison between multiple units with and without the programme, controlling for other factors, or using comparison units that evidence only minor differences

Newburn, T. (2008) (2nd ed) The Handbook of Policing. Devon. Willan Publishing

Putnam, R (2000) Bowling Alone: Touchstone, New York

Reiner, R. (2000) The Politics of the Police. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Ritchie, S. (in press) “Community Engagement, Democracy and Public Policy: a Practitioner Perspective” in Wankhade, P. and Weir D. (Eds). The Police as an Emergency Service: Leadership and Management Perspectives, Springer: New York.

Rosenfeld, R., Messner, S. F. and Baumer, E. P. (2001). ‘Social Capital and Homicide.’ Social Forces80(1): 283–310.

Waters, I. (1996) Quality of Service: Politics or Paradigm Shift? Chapter in Leishman, F., Loveday, B., Savage, S.P. (eds.) (1st ed) (1999) Core Issues in Policing. Singapore. Longman Group